Considerations On Cost Disease

February 9, 2017

I

Tyler Cowen writes about cost disease. I’d previously heard the term used to refer only to a specific theory of why costs are increasing, involving labor becoming more efficient in some areas than others. Cowen seems to use it indiscriminately to refer to increasing costs in general – which I guess is fine, goodness knows we need a word for that.

Cowen assumes his readers already understand that cost disease exists. I don’t know if this is true. My impression is that most people still don’t know about cost disease, or don’t realize the extent of it. So I thought I would make the case for the cost disease in the sectors Tyler mentions – health care and education – plus a couple more.

First let’s look at primary education:

There was some argument about the style of this graph, but as per Politifact the basic claim is true. Per student spending has increased about 2.5x in the past forty years even after adjusting for inflation.

At the same time, test scores have stayed relatively stagnant. You can see the full numbers here, but in short, high school students’ reading scores went from 285 in 1971 to 287 today – a difference of 0.7%.

There is some heterogenity across races – white students’ test scores increased 1.4% and minority students’ scores by about 20%. But it is hard to credit school spending for the minority students’ improvement, which occurred almost entirely during the period from 1975-1985. School spending has been on exactly the same trajectory before and after that time, and in white and minority areas, suggesting that there was something specific about that decade which improved minority (but not white) scores. Most likely this was the general improvement in minorities’ conditions around that time, giving them better nutrition and a more stable family life. It’s hard to construct a narrative where it was school spending that did it – and even if it did, note that the majority of the increase in school spending happened from 1985 on, and demonstrably helped neither whites nor minorities.

I discuss this phenomenon more here and here, but the summary is: no, it’s not just because of special ed; no, it’s not just a factor of how you measure test scores; no, there’s not a “ceiling effect”. Costs really did more-or-less double without any concomitant increase in measurable quality.

So, imagine you’re a poor person. White, minority, whatever. Which would you prefer? Sending your child to a 2016 school? Or sending your child to a 1975 school, and getting a check for $5,000 every year?

I’m proposing that choice because as far as I can tell that is the stakes here. 2016 schools have whatever tiny test score advantage they have over 1975 schools, and cost $5000/year more, inflation adjusted. That $5000 comes out of the pocket of somebody – either taxpayers, or other people who could be helped by government programs.

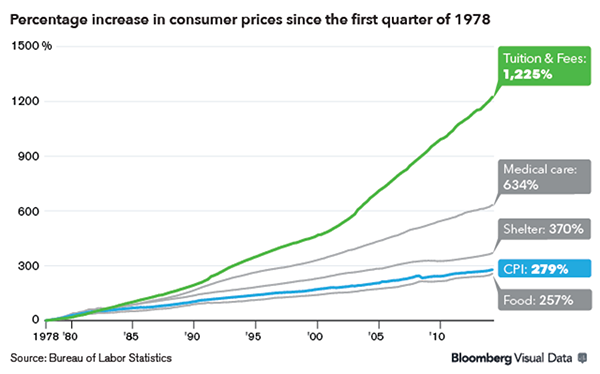

Second, college is even worse:

Note this is not adjusted for inflation; see link below for adjusted figures

Inflation-adjusted cost of a university education was something like $2000/year in 1980. Now it’s closer to $20,000/year. No, it’s not because of decreased government funding, and there are similar trajectories for public and private schools.

I don’t know if there’s an equivalent of “test scores” measuring how well colleges perform, so just use your best judgment. Do you think that modern colleges provide $18,000/year greater value than colleges did in your parents’ day? Would you rather graduate from a modern college, or graduate from a college more like the one your parents went to, plus get a check for $72,000?

(or, more realistically, have $72,000 less in student loans to pay off)

Was your parents’ college even noticeably worse than yours? My parents sometimes talk about their college experience, and it seems to have had all the relevant features of a college experience. Clubs. Classes. Professors. Roommates. I might have gotten something extra for my $72,000, but it’s hard to see what it was.

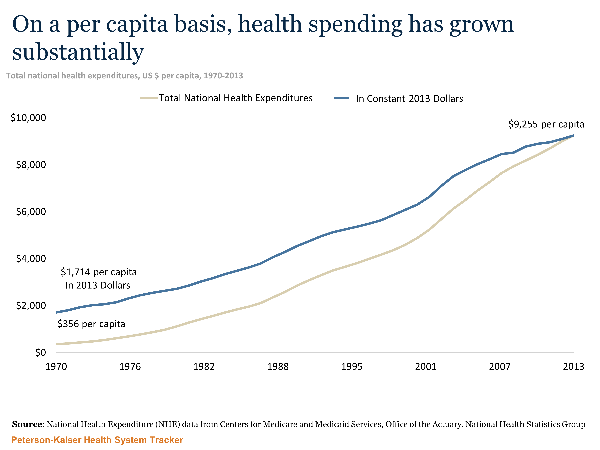

Third, health care. The graph is starting to look disappointingly familiar:

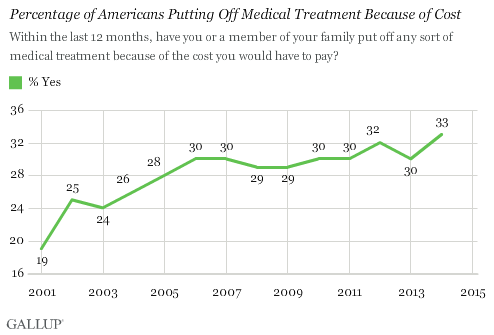

The cost of health care has about quintupled since 1970. It’s actually been rising since earlier than that, but I can’t find a good graph; it looks like it would have been about $1200 in today’s dollars in 1960, for an increase of about 800% in those fifty years.

This has had the expected effects. The average 1960 worker spent ten days’ worth of their yearly paycheck on health insurance; the average modern worker spends sixty days’ worth of it, a sixth of their entire earnings.

Or not.

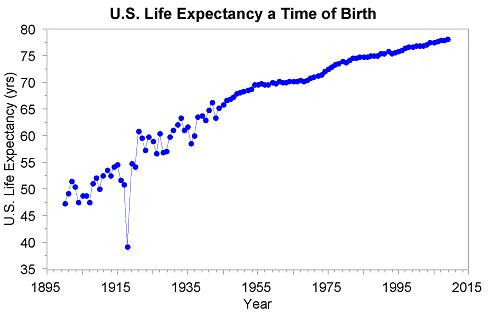

This time I can’t say with 100% certainty that all this extra spending has been for nothing. Life expectancy has gone way up since 1960:

Extra bonus conclusion: the Spanish flu was really bad

But a lot of people think that life expectancy depends on other things a lot more than healthcare spending. Sanitation, nutrition, quitting smoking, plus advances in health technology that don’t involve spending more money. ACE inhibitors (invented in 1975) are great and probably increased lifespan a lot, but they cost $20 for a year’s supply and replaced older drugs that cost about the same amount.

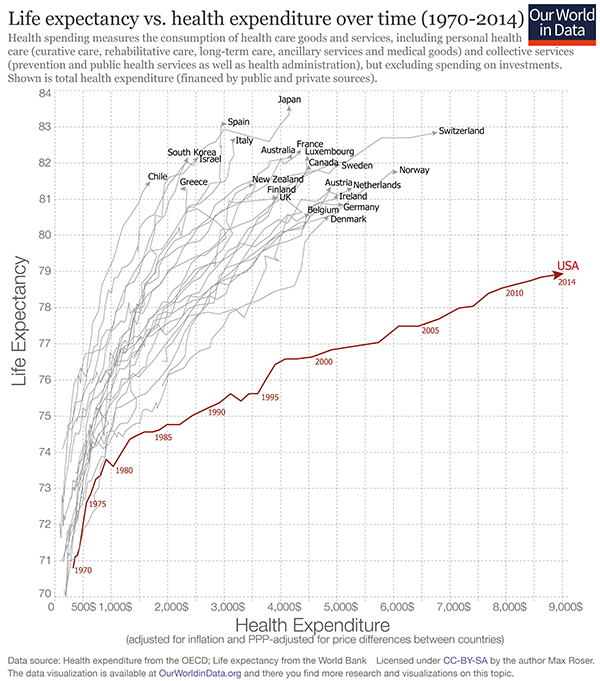

In terms of calculating how much lifespan gain healthcare spending has produced, we have a couple of options. Start with by country:

Countries like South Korea and Israel have about the same life expectancy as the US but pay about 25% of what we do. Some people use this to prove the superiority of centralized government health systems, although Random Critical Analysis has an alternative perspective. In any case, it seems very possible to get the same improving life expectancies as the US without octupling health care spending.

The Netherlands increased their health budget by a lot around 2000, sparking a bunch of studies on whether that increased life expectancy or not. There’s a good meta-analysis here, which lists six studies trying to calculate how much of the change in life expectancy was due to the large increases in health spending during this period. There’s a broad range of estimates: 0.3%, 1.8%, 8.0%, 17.2%, 22.1%, 27.5% (I’m taking their numbers for men; the numbers for women are pretty similar). They also mention two studies that they did not officially include; one finding 0% effect and one finding 50% effect (I’m not sure why these studies weren’t included). They add:

In none of these studies is the issue of reverse causality addressed; sometimes it is not even mentioned. This implies that the effect of health care spending on mortality may be overestimated.

They say:

Based on our review of empirical studies, we conclude that it is likely that increased health care spending has contributed to the recent increase in life expectancy in the Netherlands. Applying the estimates form published studies to the observed increase in health care spending in the Netherlands between 2000 and 2010 [of 40%] would imply that 0.3% to almost 50% of the increase in life expectancy may have been caused by increasing health care spending. An important reason for the wide range in such estimates is that they all include methodological problems highlighted in this paper. However, this wide range inicates that the counterfactual study by Meerding et al, which argued that 50% of the increase in life expectancy in the Netherlands since the 1950s can be attributed to medical care, can probably be interpreted as an upper bound.

It’s going to be completely irresponsible to try to apply this to the increase in health spending in the US over the past 50 years, since this is probably different at every margin and the US is not the Netherlands and the 1950s are not the 2010s. But if we irresponsibly take their median estimate and apply it to the current question, we get that increasing health spending in the US has been worth about one extra year of life expectancy. This study attempts to directly estimate a GDP corresponds to an increase of 0.05 years life expectancy. That would suggest a slightly different number of 0.65 years life expectancy gained by healthcare spending since 1960)

If these numbers seem absurdly low, remember all of those controlled experiments where giving people insurance doesn’t seem to make them much healthier in any meaningful way.

Or instead of slogging through the statistics, we can just ask the same question as before. Do you think the average poor or middle-class person would rather:

- Get modern health care

- Get the same amount of health care as their parents’ generation, but with modern technology like ACE inhibitors, and also earn $8000 extra a year

Fourth, we see similar effects in infrastructure. The first New York City subway opened around 1900. Various sources list lengths from 10 to 20 miles and costs from $30 million to $60 million dollars – I think my sources are capturing it at different stages of construction with different numbers of extensions. In any case, it suggests costs of between $1.5 million to $6 million dollars/mile = $1-4 million per kilometer. That looks like it’s about the inflation-adjusted equivalent of $100 million/kilometer today, though I’m very uncertain about that estimate. In contrast, Vox notes that a new New York subway line being opened this year costs about $2.2 billion per kilometer, suggesting a cost increase of twenty times – although I’m very uncertain about this estimate.

Things become clearer when you compare them country-by-country. The same Vox article notes that Paris, Berlin, and Copenhagen subways cost about $250 million per kilometer, almost 90% less. Yet even those European subways are overpriced compared to Korea, where a kilometer of subway in Seoul costs $40 million/km (another Korean subway project cost $80 million/km). This is a difference of 50x between Seoul and New York for apparently comparable services. It suggests that the 1900s New York estimate above may have been roughly accurate if their efficiency was roughly in line with that of modern Europe and Korea.

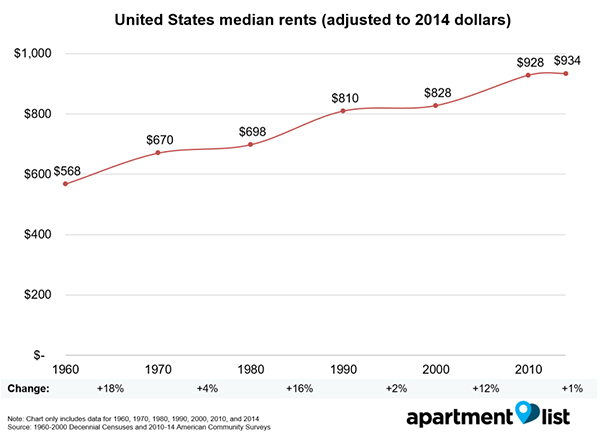

Fifth, housing (source):

Most of the important commentary on this graph has already been said, but I would add that optimistic takes like this one by the American Enterprise Institute are missing some of the dynamic. Yes, homes are bigger than they used to be, but part of that is zoning laws which make it easier to get big houses than small houses. There are a lot of people who would prefer to have a smaller house but don’t. When I first moved to Michigan, I lived alone in a three bedroom house because there were no good one-bedroom houses available near my workplace and all of the apartments were loud and crime-y.

Or, once again, just ask yourself: do you think most poor and middle class people would rather:

- Rent a modern house/apartment

- Rent the sort of house/apartment their parents had, for half the cost

II

So, to summarize: in the past fifty years, education costs have doubled, college costs have dectupled, health insurance costs have dectupled, subway costs have at least dectupled, and housing costs have increased by about fifty percent. US health care costs about four times as much as equivalent health care in other First World countries; US subways cost about eight times as much as equivalent subways in other First World countries.

I worry that people don’t appreciate how weird this is. I didn’t appreciate it for a long time. I guess I just figured that Grandpa used to talk about how back in his day movie tickets only cost a nickel; that was just the way of the world. But all of the numbers above are inflation-adjusted. These things have dectupled in cost even after you adjust for movies costing a nickel in Grandpa’s day. They have really, genuinely dectupled in cost, no economic trickery involved.

And this is especially strange because we expect that improving technology and globalization ought to cut costs. In 1983, the first mobile phone cost $4,000 – about $10,000 in today’s dollars. It was also a gigantic piece of crap. Today you can get a much better phone for $100. This is the right and proper way of the universe. It’s why we fund scientists, and pay businesspeople the big bucks.

But things like college and health care have still had their prices dectuple. Patients can now schedule their appointments online; doctors can send prescriptions through the fax, pharmacies can keep track of medication histories on centralized computer systems that interface with the cloud, nurses get automatic reminders when they’re giving two drugs with a potential interaction, insurance companies accept payment through credit cards – and all of this costs ten times as much as it did in the days of punch cards and secretaries who did calculations by hand.

It’s actually even worse than this, because we take so many opportunities to save money that were unavailable in past generations. Underpaid foreign nurses immigrate to America and work for a song. Doctors’ notes are sent to India overnight where they’re transcribed by sweatshop-style labor for pennies an hour. Medical equipment gets manufactured in goodness-only-knows which obscure Third World country. And it still costs ten times as much as when this was all made in the USA – and that back when minimum wages were proportionally higher than today.

And it’s actually even worse than this. A lot of these services have decreased in quality, presumably as an attempt to cut costs even further. Doctors used to make house calls; even when I was young in the ’80s my father would still go to the houses of difficult patients who were too sick to come to his office. This study notes that for women who give birth in the hospital, “the standard length of stay was 8 to 14 days in the 1950s but declined to less than 2 days in the mid-1990s”. The doctors I talk to say this isn’t because modern women are healthier, it’s because they kick them out as soon as it’s safe to free up beds for the next person. Historic records of hospital care generally describe leisurely convalescence periods and making sure somebody felt absolutely well before letting them go; this seems bizarre to anyone who has participated in a modern hospital, where the mantra is to kick people out as soon as they’re “stable” ie not in acute crisis.

If we had to provide the same quality of service as we did in 1960, and without the gains from modern technology and globalization, who even knows how many times more health care would cost? Fifty times more? A hundred times more?

And the same is true for colleges and houses and subways and so on.

III

The existing literature on cost disease focuses on the Baumol effect. Suppose in some underdeveloped economy, people can choose either to work in a factory or join an orchestra, and the salaries of factory workers and orchestra musicians reflect relative supply and demand and profit in those industries. Then the economy undergoes a technological revolution, and factories can produce ten times as many goods. Some of the increased productivity trickles down to factory workers, and they earn more money. Would-be musicians leave the orchestras behind to go work in the higher-paying factories, and the orchestras have to raise their prices if they want to be assured enough musicians. So tech improvements in the factory sectory raise prices in the orchestra sector.

We could tell a story like this to explain rising costs in education, health care, etc. If technology increases productivity for skilled laborers in other industries, then less susceptible industries might end up footing the bill since they have to pay their workers more.

There’s only one problem: health care and education aren’t paying their workers more; in fact, quite the opposite.

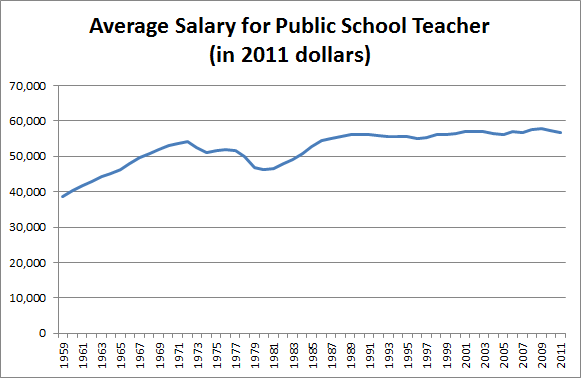

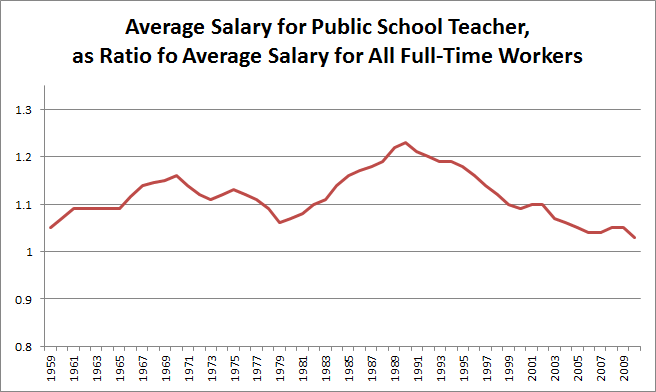

Here are teacher salaries over time ( source):

Teacher salaries are relatively flat adjusting for inflation. But salaries for other jobs are increasing modestly relative to inflation. So teacher salaries relative to other occupations’ salaries are actually declining.

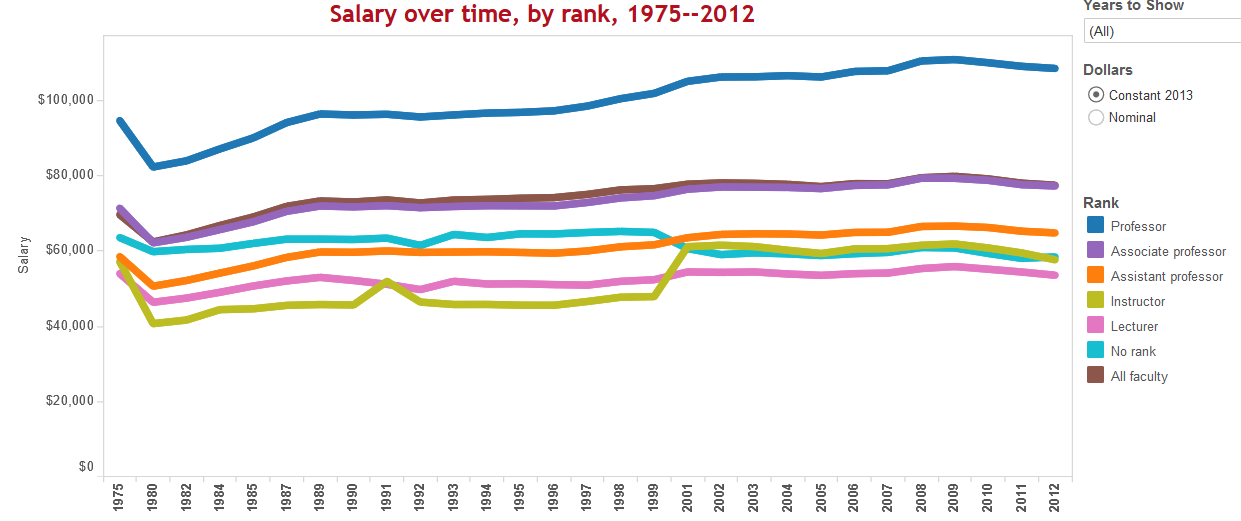

Here’s a similar graph for professors ( source):

Professor salaries are going up a little, but again, they’re probably losing position relative to the average occupation. Also, note that although the average salary of each type of faculty is stable or increasing, the average salary of all faculty is going down. No mystery here – colleges are doing everything they can to switch from tenured professors to adjuncts, who complain of being overworked and abused while making about the same amount as a Starbucks barista.

This seems to me a lot like the case of the hospitals cutting care for new mothers. The price of the service dectuples, yet at the same time the service has to sacrifice quality in order to control costs.

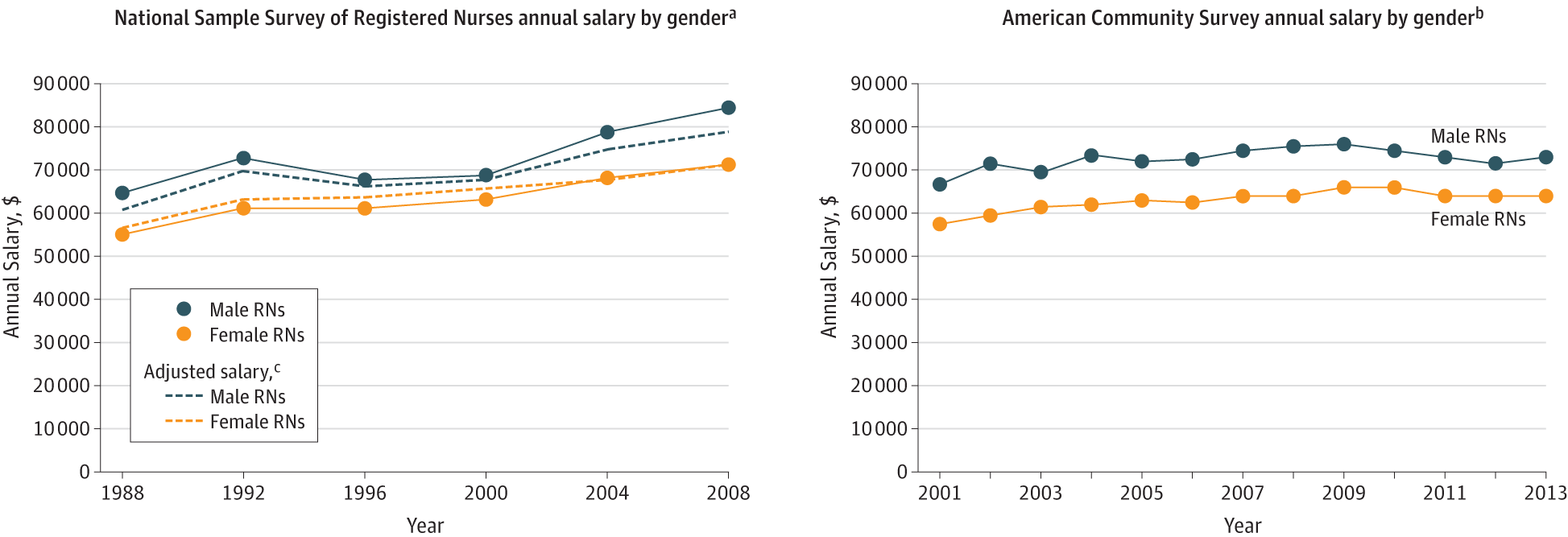

And speaking of hospitals, here’s the graph for nurses ( source):

Female nurses’ salaries went from about $55,000 in 1988 to $63,000 in 2013. This is probably around the average wage increase during that time. Also, some of this reflects changes in education: in the 1980s only 40% of nurses had a degree; by 2010, about 80% did.

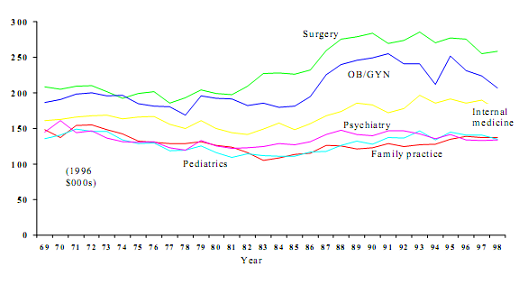

And for doctors (source)

Stable again! Except that a lot of doctors’ salaries now go to paying off their medical school debt, which has been ballooning like everything eles.

I don’t have a similar graph for subway workers, but come on. The overall pictures is that health care and education costs have managed to increase by ten times without a single cent of the gains going to teachers, doctors, or nurses. Indeed these professions seem to have lost ground salary-wise relative to others.

I also want to add some anecdote to these hard facts. My father is a doctor and my mother is a teacher, so I got to hear a lot about how these professions have changed over the past generation. It seems at least a little like the adjunct story, although without the clearly defined “professor vs. adjunct” dichotomy that makes it so easy to talk about. Doctors are really, really, really unhappy. When I went to medical school, some of my professors would tell me outright that they couldn’t believe anyone would still go into medicine with all of the new stresses and demands placed on doctors. This doesn’t seem to be limited to one medical school. Wall Street Journal: Why Doctors Are Sick Of Their Profession – “American physicians are increasingly unhappy with their once-vaunted profession, and that malaise is bad for their patients”. The Daily Beast: How Being A Doctor Became The Most Miserable Profession – “Being a doctor has become a miserable and humiliating undertaking. Indeed, many doctors feel that America has declared war on physicians”. Forbes: Why Are Doctors So Unhappy? – “Doctors have become like everyone else: insecure, discontent and scared about the future.” Vox: Only Six Percent Of Doctors Are Happy With Their Jobs. Al Jazeera America: Here’s Why Nine Out Of Ten Doctors Wouldn’t Recommend Medicine As A Profession. Read these articles and they all say the same thing that all the doctors I know say – medicine used to be a well-respected, enjoyable profession where you could give patients good care and feel self-actualized. Now it kind of sucks.

Meanwhile, I also see articles like this piece from NPR saying teachers are experiencing historic stress levels and up to 50% say their job “isn’t worth it”. Teacher job satisfaction is at historic lows. And the veteran teachers I know say the same thing as the veteran doctors I know – their jobs used to be enjoyable and make them feel like they were making a difference; now they feel overworked, unappreciated, and trapped in mountains of paperwork.

It might make sense for these fields to become more expensive if their employees’ salaries were increasing. And it might make sense for salaries to stay the same if employees instead benefitted from lower workloads and better working conditions. But neither of these are happening.

IV

So what’s going on? Why are costs increasing so dramatically? Some possible answers:

First, can we dismiss all of this as an illusion? Maybe adjusting for inflation is harder than I think. Inflation is an average, so some things have to have higher-than-average inflation; maybe it’s education, health care, etc. Or maybe my sources have the wrong statistics.

But I don’t think this is true. The last time I talked about this problem, someone mentioned they’re running a private school which does just as well as public schools but costs only $3000/student/year, a fourth of the usual rate. Marginal Revolution notes that India has a private health system that delivers the same quality of care as its public system for a quarter of the cost. Whenever the same drug is provided by the official US health system and some kind of grey market supplement sort of thing, the grey market supplement costs between a fifth and a tenth as much; for example, Google’s first hit for Deplin®, official prescription L-methylfolate, costs $175 for a month’s supply ; unregulated L-methylfolate supplement delivers the same dose for about $30. And this isn’t even mentioning things like the $1 bag of saline that costs $700 at hospitals. Since it seems like it’s not too hard to do things for a fraction of what we currently do things for, probably we should be less reluctant to believe that the cost of everything is really inflated.

Second, might markets just not work? I know this is kind of an extreme question to ask in a post on economics, but maybe nobody knows what they’re doing in a lot of these fields and people can just increase costs and not suffer any decreased demand because of it. Suppose that people proved beyond a shadow of a doubt that Khan Academy could teach you just as much as a normal college education, but for free. People would still ask questions like – will employers accept my Khan Academy degree? Will it look good on a resume? Will people make fun of me for it? The same is true of community colleges, second-tier colleges, for-profit colleges, et cetera. I got offered a free scholarship to a mediocre state college, and I turned it down on the grounds that I knew nothing about anything and maybe years from now I would be locked out of some sort of Exciting Opportunity because my college wasn’t prestigious enough. Assuming everyone thinks like this, can colleges just charge whatever they want?

Likewise, my workplace offered me three different health insurance plans, and I chose the middle-expensiveness one, on the grounds that I had no idea how health insurance worked but maybe if I bought the cheap one I’d get sick and regret my choice, and maybe if I bought the expensive one I wouldn’t be sick and regret my choice. I am a doctor, my employer is a hospital, and the health insurance was for treatment in my own health system. The moral of the story is that I am an idiot. The second moral of the story is that people probably are not super-informed health care consumers.

This can’t be pure price-gouging, since corporate profits haven’t increased nearly enough to be where all the money is going. But a while ago a commenter linked me to the Delta Cost Project, which scrutinizes the exact causes of increasing college tuition. Some of it is the administrative bloat that you would expect. But a lot of it is fun “student life” types of activities like clubs, festivals, and paying Milo Yiannopoulos to speak and then cleaning up after the ensuing riots. These sorts of things improve the student experience, but I’m not sure that the average student would rather go to an expensive college with clubs/festivals/Milo than a cheap college without them. More important, it doesn’t really seem like the average student is offered this choice.

This kind of suggests a picture where colleges expect people will pay whatever price they set, so they set a very high price and then use the money for cool things and increasing their own prestige. Or maybe clubs/festivals/Milo become such a signal of prestige that students avoid colleges that don’t comply since they worry their degrees won’t be respected? Some people have pointed out that hospitals have switched from many-people-all-in-a-big-ward to private rooms. Once again, nobody seems to have been offered the choice between expensive hospitals with private rooms versus cheap hospitals with roommates. It’s almost as if industries have their own reasons for switching to more-bells-and-whistles services that people don’t necessarily want, and consumers just go along with it because for some reason they’re not exercising choice the same as they would in other markets.

(this article on the Oklahoma City Surgery Center might be about a partial corrective for this kind of thing)

Third, can we attribute this to the inefficiency of government relative to private industry? I don’t think so. The government handles most primary education and subways, and has its hand in health care. But we know that for-profit hospitals aren’t much cheaper than government hospitals, and that private schools usually aren’t much cheaper (and are sometimes more expensive) than government schools. And private colleges cost more than government-funded ones.

Fourth, can we attribute it to indirect government intervention through regulation, which public and private companies alike must deal with? This seems to be at least part of the story in health care, given how much money you can save by grey-market practices that avoid the FDA. It’s harder to apply it to colleges, though some people have pointed out regulations like Title IX that affect the educational sector.

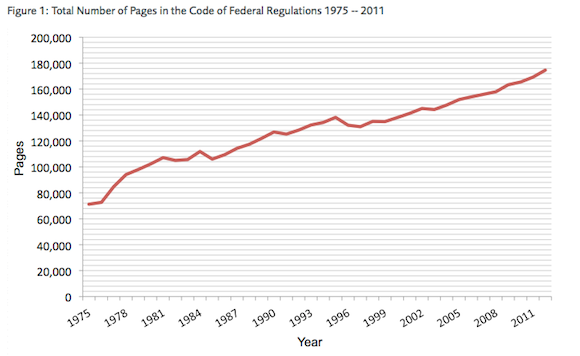

One factor that seems to speak out against this is that starting with Reagan in 1980, and picking up steam with Gingrich in 1994, we got an increasing presence of Republicans in government who declared war on overregulation – but the cost disease proceeded unabated. This is suspicious, but in fairness to the Republicans, they did sort of fail miserably at deregulating things. “The literal number of pages in the regulatory code” is kind of a blunt instrument, but it doesn’t exactly inspire confidence in the Republicans’ deregulation efforts:

Here’s a more interesting (and more fun) argument against regulations being to blame: what about pet health care? Veterinary care is much less regulated than human health care, yet its cost is rising as fast (or faster) than that of the human medical system ( popular article, study). I’m not sure what to make of this.

Fifth, might the increased regulatory complexity happen not through literal regulations, but through fear of lawsuits? That is, might institutions add extra layers of administration and expense not because they’re forced to, but because they fear being sued if they don’t and then something goes wrong?

I see this all the time in medicine. A patient goes to the hospital with a heart attack. While he’s recovering, he tells his doctor that he’s really upset about all of this. Any normal person would say “You had a heart attack, of course you’re upset, get over it.” But if his doctor says this, and then a year later he commits suicide for some unrelated reason, his family can sue the doctor for “not picking up the warning signs” and win several million dollars. So now the doctor consults a psychiatrist, who does an hour-long evaluation, charges the insurance company $500, and determines using her immense clinical expertise that the patient is upset because he just had a heart attack.

Those outside the field have no idea how much of medicine is built on this principle. People often say that the importance of lawsuits to medical cost increases is overrated because malpractice insurance doesn’t cost that much, but the situation above would never look lawsuit-related; the whole thing only works because everyone involved documents it as well-justified psychiatric consult to investigate depression. Apparently some studies suggest this isn’t happening, but all they do is survey doctors, and with all due respect all the doctors I know say the opposite.

This has nothing to do with government regulations (except insofar as these make lawsuits easier or harder), but it sure can drive cost increases, and it might apply to fields outside medicine as well.

Sixth, might we have changed our level of risk tolerance? That is, might increased caution be due not purely to lawsuitphobia, but to really caring more about whether or not people are protected? I read stuff every so often about how playgrounds are becoming obsolete because nobody wants to let kids run around unsupervised on something with sharp edges. Suppose that one in 10,000 kids get a horrible playground-related injury. Is it worth making playgrounds cost twice as much and be half as fun in order to decrease that number to one in 100,000? This isn’t a rhetorical question; I think different people can have legitimately different opinions here (though there are probably some utilitarian things we can do to improve them).

To bring back the lawsuit point, some of this probably relates to a difference between personal versus institutional risk tolerance. Every so often, an elderly person getting up to walk to the bathroom will fall and break their hip. This is a fact of life, and elderly people deal with it every day. Most elderly people I know don’t spend thousands of dollars fall-proofing the route from their bed to their bathroom, or hiring people to watch them at every moment to make sure they don’t fall, or buy a bedside commode to make bathroom-related falls impossible. This suggests a revealed preference that elderly people are willing to tolerate a certain fall probability in order to save money and convenience. Hospitals, which face huge lawsuits if any elderly person falls on the premises, are not willing to tolerate that probability. They put rails on elderly people’s beds, place alarms on them that will go off if the elderly person tries to leave the bed without permission, and hire patient care assistants who among other things go around carefully holding elderly people upright as they walk to the bathroom (I assume this job will soon require at least a master’s degree). As more things become institutionalized and the level of acceptable institutional risk tolerance becomes lower, this could shift the cost-risk tradeoff even if there isn’t a population-level trend towards more risk-aversion.

Seventh, might things cost more for the people who pay because so many people don’t pay? This is somewhat true of colleges, where an increasing number of people are getting in on scholarships funded by the tuition of non-scholarship students. I haven’t been able to find great statistics on this, but one argument against: couldn’t a college just not fund scholarships, and offer much lower prices to its paying students? I get that scholarships are good and altruistic, but it would be surprising if every single college thought of its role as an altruistic institution, and cared about it more than they cared about providing the same service at a better price. I guess this is related to my confusion about why more people don’t open up colleges. Maybe this is the “smart people are rightly too scared and confused to go to for-profit colleges, and there’s not enough ability to discriminate between the good and the bad ones to make it worthwhile to found a good one” thing again.

This also applies in health care. Our hospital (and every other hospital in the country) has some “frequent flier” patients who overdose on meth at least once a week. They comes in, get treated for their meth overdose (we can’t legally turn away emergency cases), get advised to get help for their meth addiction (without the slightest expectation that they will take our advice) and then get discharged. Most of them are poor and have no insurance, but each admission costs a couple of thousand dollars. The cost gets paid by a combination of taxpayers and other hospital patients with good insurance who get big markups on their own bills.

Eighth, might total compensation be increasing even though wages aren’t? There definitely seems to be a pensions crisis, especially in a lot of government work, and it’s possible that some of this is going to pay the pensions of teachers, etc. My understanding is that in general pensions aren’t really increasing much faster than wages, but this might not be true in those specific industries. Also, this might pass the buck to the question of why we need to spend more on pensions now than in the past. I don’t think increasing life expectancy explains all of this, but I might be wrong.

IV

I mentioned politics briefly above, but they probably deserve more space here. Libertarian-minded people keep talking about how there’s too much red tape and the economy is being throttled. And less libertarian-minded people keep interpreting it as not caring about the poor, or not understanding that government has an important role in a civilized society, or as a “dog whistle” for racism, or whatever. I don’t know why more people don’t just come out and say “LOOK, REALLY OUR MAIN PROBLEM IS THAT ALL THE MOST IMPORTANT THINGS COST TEN TIMES AS MUCH AS THEY USED TO FOR NO REASON, PLUS THEY SEEM TO BE GOING DOWN IN QUALITY, AND NOBODY KNOWS WHY, AND WE’RE MOSTLY JUST DESPERATELY FLAILING AROUND LOOKING FOR SOLUTIONS HERE.” State that clearly, and a lot of political debates take on a different light.

For example: some people promote free universal college education, remembering a time when it was easy for middle class people to afford college if they wanted it. Other people oppose the policy, remembering a time when people didn’t depend on government handouts. Both are true! My uncle paid for his tuition at a really good college just by working a pretty easy summer job – not so hard when college cost a tenth of what it did now. The modern conflict between opponents and proponents of free college education is over how to distribute our losses. In the old days, we could combine low taxes with widely available education. Now we can’t, and we have to argue about which value to sacrifice.

Or: some people get upset about teachers’ unions, saying they must be sucking the “dynamism” out of education because of increasing costs. Others people fiercely defend them, saying teachers are underpaid and overworked. Once again, in the context of cost disease, both are obviously true. The taxpayers are just trying to protect their right to get education as cheaply as they used to. The teachers are trying to protect their right to make as much money as they used to. The conflict between the taxpayers and the teachers’ unions is about how to distribute losses; somebody is going to have to be worse off than they were a generation ago, so who should it be?

And the same is true to greater or lesser degrees in the various debates over health care, public housing, et cetera.

Imagine if tomorrow, the price of water dectupled. Suddenly people have to choose between drinking and washing dishes. Activists argue that taking a shower is a basic human right, and grumpy talk show hosts point out that in their day, parents taught their children not to waste water. A coalition promotes laws ensuring government-subsidized free water for poor families; a Fox News investigative report shows that some people receiving water on the government dime are taking long luxurious showers. Everyone gets really angry and there’s lots of talk about basic compassion and personal responsibility and whatever but all of this is secondary to why does water costs ten times what it used to? I think this is the basic intuition behind so many people, even those who genuinely want to help the poor, are afraid of “tax and spend” policies. In the context of cost disease, these look like industries constantly doubling, tripling, or dectupling their price, and the government saying “Okay, fine,” and increasing taxes however much it costs to pay for whatever they’re demanding now.

If we give everyone free college education, that solves a big social problem. It also locks in a price which is ten times too high for no reason. This isn’t fair to the government, which has to pay ten times more than it should. It’s not fair to the poor people, who have to face the stigma of accepting handouts for something they could easily have afforded themselves if it was at its proper price. And it’s not fair to future generations if colleges take this opportunity to increase the cost by twenty times, and then our children have to subsidize that.

I’m not sure how many people currently opposed to paying for free health care, or free college, or whatever, would be happy to pay for health care that cost less, that was less wasteful and more efficient, and whose price we expected to go down rather than up with every passing year. I expect it would be a lot.

And if it isn’t, who cares? The people who want to help the poor have enough political capital to spend eg $500 billion on Medicaid; if that were to go ten times further, then everyone could get the health care they need without any more political action needed. If some government program found a way to give poor people good health insurance for a few hundred dollars a year, college tuition for about a thousand, and housing for only two-thirds what it costs now, that would be the greatest anti-poverty advance in history. That program is called “having things be as efficient as they were a few decades ago”.

V

In 1930, economist John Maynard Keynes predicted that his grandchildrens’ generation would have a 15 hour work week. At the time, it made sense. GDP was rising so quickly that anyone who could draw a line on a graph could tell that our generation would be four or five times richer than his. And the average middle-class person in his generation felt like they were doing pretty well and had most of what they needed. Why wouldn’t they decide to take some time off and settle for a lifestyle merely twice as luxurious as Keynes’ own?

Keynes was sort of right. GDP per capita is 4-5x greater today than in his time. Yet we still work forty hour weeks, and some large-but-inconsistently-reported percent of Americans ( 76 ? 55? 47?) still live paycheck to paycheck.

And yes, part of this is because inequality is increasing and most of the gains are going to the rich. But this alone wouldn’t be a disaster; we’d get to Keynes’ utopia a little slower than we might otherwise, but eventually we’d get there. Most gains going to the rich means at least some gains are going to the poor. And at least there’s a lot of mainstream awareness of the problem.

I’m more worried about the part where the cost of basic human needs goes up faster than wages do. Even if you’re making twice as much money, if your health care and education and so on cost ten times as much, you’re going to start falling behind. Right now the standard of living isn’t just stagnant, it’s at risk of declining, and a lot of that is student loans and health insurance costs and so on.

What’s happening? I don’t know and I find it really scary.