Meat Your Doom

October 28, 2015

Epistemic status: Very dirty and approximate, but I think roughly correct. Check my calculations and tell me if I’m wrong.

I

A recent formative experience: a seriously ill patient came in and I recommended a strong psychiatric drug. She looked it up online and told me she wouldn’t take it because was associated with an X% increase in mortality.

“But,” I pointed out, “you’re really miserable.”

“But I don’t want to die!”

So I looked it up, did the calculations, and found that it would on average take a couple of months off her life. And I asked her, “Which would you prefer – living 80 years severely ill, or living 79.5 years feeling mostly okay?”

She still wasn’t convinced, so I asked her if she ate cookies. She said yes, almost every day. I told her that the cookies were probably taking more time off her life than the medication would, and I assured her the medication would probably add more value to her life than cookies.

She took the drug.

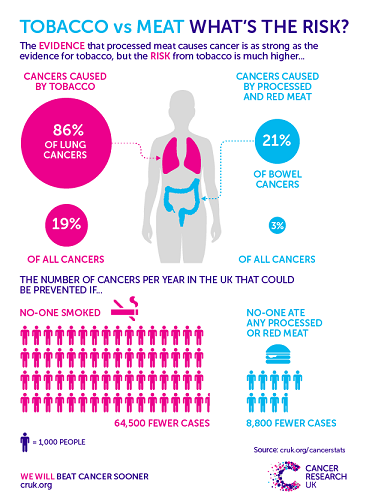

I thought of this the other day when everyone started sharing that study about meat causing colon cancer. A lot of people used headlines like Processed Meats Rank Alongside Smoking As Cancer Causes. This was very correctly debunked by infographics like this one:

But I feel like this leaves something to be desired. Eating meat is not as bad as smoking. But that’s still a lot of room for it to be bad. Can we quantify the risk better?

From the BBC article: “‘[There would be] one extra case of bowel cancer in 100 lifetime bacon-eaters,’ argues Sir David Spiegelhalter, a risk professor from the University of Cambridge.”

This teaches us something important: “risk professor” is an awesome job title and “David Spiegelhalter, Risk Professor” ought to be a BBC television show starring Harrison Ford.

But also: use absolute risk instead of relative risk! “21% of bowel cancers are caused by meat” doesn’t give you a really good handle on how worried you should be. “One extra case of bowel-cancer in 100 lifetime bacon-eaters” is better.

But let me try to give even more perspective. A bit less than half of colon cancers are fatal. So one extra case per hundred means if you eat bacon daily then there’s an 0.4% chance you will die from a cancer you would not otherwise have gotten.

The average age at diagnosis of colon cancer is 69; the average life expectancy is 79. Sweeping a lot of complexity under the rug and taking a very liberal estimate, the average death from colon cancer costs you ten years of your life.

Multiply out and an 0.4% chance of losing 10 years means that you lose on average two weeks.

Suppose that every case of cancer, fatal and non-fatal alike, causes you additional non-death-related distress equal to two years of your life. That’s about another week.

So overall, if you eat processed meat every day your entire life, you’ll lose about three weeks of life expectancy from colon cancer. That means each serving of meat costs you a minute of your life. You probably lose twenty times that amount just cooking and preparing it.

II

Note that I am not saying “eating meat will only decrease your lifespan by three weeks”. That is the amount that we have clear evidence for, from this study. It is an example of why this study needs to be put in context so that you don’t worry about it too much.

There are nevertheless a lot of other studies that suggest greater risks, mostly cardiovascular or metabolic. For example, as per this article, some studies suggest that a serving of red meat per day increases mortality 13%, and a serving of processed meat per day increases it 20%. But it also quotes another study of half a million people that finds meat to be slightly protective (sigh) and finds a higher all-cause mortality in the non-meat-eaters.

Whatever. Forget the object-level question for a minute. What are we to make of a claim like “processed meat increases mortality 20%”?

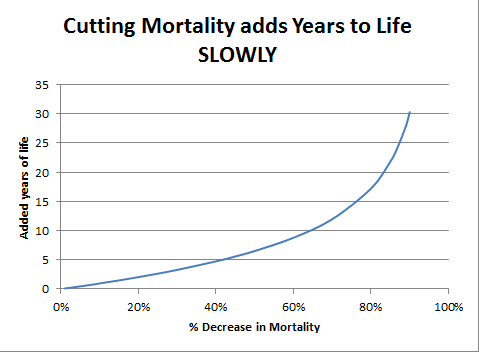

If you’re like me, you want to think “Okay, average life expectancy is eighty years, subtract 20% off of that, and you get 64 years. I’ll live 64 years if I eat bacon every day.” WRONG. Mortality rates are much more complicated, but the key insight is that very few people die when they’re young. If you have approximately a 0% chance of dying at age 30, then adding 20% to 0 is still 0. Chance of mortality creeps upward very slowly and so even large changes in mortality barely affect the underlying distribution. The only good presentation of this I have ever seen anywhere is on Josh Mitteldorf’s blog, which includes the following chart:

This is decrease and we’re talking increase, but but it shouldn’t make much difference here. A 20% increase in mortality isn’t going to bring you from 80 to 64. It’ll probably just bring you from 80 to 78.

Indeed, later in the BBC article, they bring in David Spiegelhalter (RISK PROFESSOR!) who explains that:

If the studies are right… you would expect someone who eats a bacon sandwich every day to live, on average, two years less than someone who does not. Pro rata, this is like losing an hour of your life for every bacon sandwich you eat. To put this into context, every time you smoke 20 cigarettes, this will take about five hours off your life.

That’s for processed meat. Red meat is safer. Also, we still don’t know if these studies are right.

This is why it’s important to distinguish between absolute and relative risk. You hear all of these scary numbers – 21% increase in bowel cancers! 20% increase in all-cause mortality! – and it sounds like you’re going to drop dead the moment you take a bite of a hot dog. And there’s always that chance. Being healthy is good. Being unhealthy is bad. But is life so dear or peace so sweet, that you’re never going to want to sacrifice an hour to have a bacon sandwich?

All these hours do add up. I’m not saying dietary recommendations aren’t important. But the recommendations are important in aggregate. If you stick to the spirit of not eating in a horribly unhealthy way, you have a lot of leeway to continue to eat specific things you like even if you know they’re not the best for you. And meat falls firmly within that category.

(though you might also want to consider how to manage the moral issues)